READ THE STORIES |

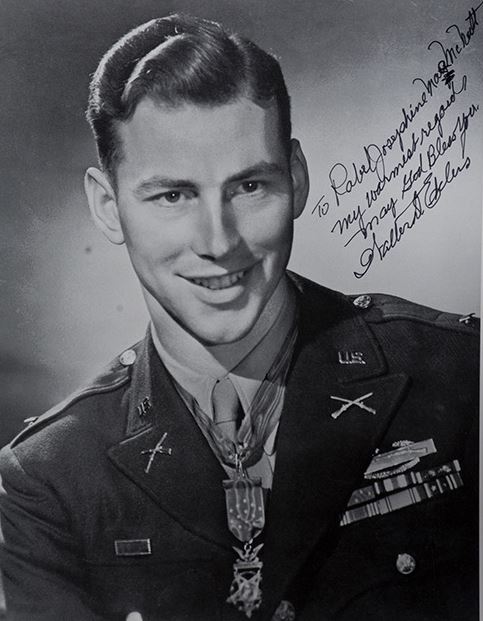

| Walter D. Ehlers, by Bill McNutt, Co-Founder and Chairman, State Funeral for WWII Veterans, August 2017 When Kansas farm boy, Walter Ehlers got to Omaha Beach it was already his third invasion. He and his brother, Roland had already invaded North Africa and Sicily. It was time for the famous Big Red One 1st Infantry Division, where the Ehlers served, to be rotated home to America. However, General Omar Bradley said that his job on June 6, 1944 to kill Germans was more important. General Bradley needed an experienced combat veteran unit on Omaha Beach next to the 29th Infantry Division. Walter and Roland joined the Army before Pearl Harbor because they were upset when they read the Germans were burning bibles and books. Walter was underage upon enlisting. In order to sign his papers, his mom made him promise to always be a Christian soldier who never harmed non-combatants. The Ehlers boys fought side by side until the U.S. military changed its policy, and the boys were placed in separate units while training for the invasion of Hitler’s Europe during the spring of 1944. Roland was killed approaching Omaha Beach when a mortar shell struck his landing craft. Walter, staff sergeant and squad leader in the 18th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division, landed between the first and second wave on June 6, 1944. “I got all my men across the beach that day. It was the best thing I ever did in my life,” he said. They fought their way off the beach during the next three days, and by June 10, they were eight miles inland near the town of Goville. Walter Ehlers was awarded the Medal of Honor for his exploits. Walter, who grew up hunting, always liked to take the point in combat. "Often times I could smell the Germans, because of their diet before I could see them." he said on many occasions. On June 9, fighting in the hedgerows, he killed four of the enemy troops. Ordering his men to fix bayonets and firing from the hip, he destroyed a machine gun nest and scattered a mortar crew. Next, he attacked a second machine gun nest, killing three more of the enemy using only his bayonet. The next morning his platoon came under intense fire from two sides. Ehlers and his Browning automatic weapon man exposed themselves to enemy fire by climbing on a mound of dirt and firing hip to hip so that the rest of the men could retreat to safety. Ehlers was shot in the side but managed to kill the German who hit him. When his automatic rifleman was badly wounded, Stg. Ehlers carried him to safely despite his own wounds. Then, he returned across the field to retrieve the Browning automatic rifle. "Each platoon only had one of these and I did not want to be killed by my own weapon!" The bullet had exited through his back into his pack where it pierced a picture of his mother, hit his entrenching tool, and blasted out the back of his pack. Today, you can view "Uncle Ehlers" Medal of Honor and his mother's picture with the bullet hole in the World War II Museum in New Orleans. Despite his wounds, he refused to be evacuated. He strapped two bandoleers of bullets across his chest, grabbed his M1 rifle and kept fighting his way East, ultimately to the Allied Victory over Germany. When the war ended, he found himself at the Czechoslovakian border, some 750 miles away. "I carried my M1 the entire way. When I became an officer I could have carried something else, but the M1 had stopping power. It never let me down," Ehlers said. Following the war, Ehlers moved to Southern California and met his wife Dorothy Decker Ehlers, at a skating rink. They had three children, including Cathy Ehlers Metclaff, who later became a Vice President at the Medal of Honor Foundation. Turning down offers to go to college or to work for corporations, he spent his working career at the Veterans Administration, helping his fellow warriors and servicemen. Always the humble soldier, many of his co-workers never knew he was a Medal of Honor recipient. Following retirement, he worked as a security guard at Disneyland where he struck a lifetime friendship with Walt Disney. He also counted Jimmy Buffett, Tom Hanks, Tom Brokaw and former President George W. Bush, as friends. Mr. Ehlers loved returning to France for D Day celebrations. He traveled to the 20th Anniversary with fellow D Day Veteran, Congressman Olin E Teague, Chairman of the House of Veterans' Affairs Committee. He spoke on behalf of all veterans at the 50th anniversary in 1994, with following remarks by President Bill Clinton. Following the 60th anniversary celebration in 2004 he and I were detained at the Amsterdam airport. President George W. Bush had given Mr. Ehlers one of the Howitzer brass cannon casings from the 21-gun salute on June 6. I helped him carry it through security, not thinking that the black power residue would set off the chemical alarms! Luckily one of the Dutch guards had served with American NATO troops and spotted Mr. Ehlers's blue Medal of Honor boutonnieres and got us through security. Mr. Ehlers is the godfather of State Funeral for World War II Veterans Co-Founder, Rabel McNutt. His death and funeral in 2014 served as the inspiration for the State Funeral for World War II Veterans. Read the full story under “History of the Organization” on the State Funeral for World War II Veterans’s website. Walter D. Ehlers is buried at the Riverside National Cemetery in Riverside, California. |

| Hershel Woodrow "Woody" Williams (born October 2, 1923) Hershel Woodrow "Woody" Williams (born October 2, 1923) is a retired United States Marine Corps warrant officer and United States Department of Veterans Affairs veterans service representative who received the United States military's highest decoration for valor—the Medal of Honor—for heroism above and beyond the call of duty during the Battle of Iwo Jima in World War II. As of the spring of 2018, he and three soldiers are the only living Medal of Honor recipients from that war. In addition, he is the only surviving Marine to have received the Medal of Honor during the Second World War, and is the only surviving Medal of Honor recipient from the Pacific theater of the war. Williams, the youngest of eleven children, was born and raised on a dairy farm in Quiet Dell, West Virginia, on October 2, 1923. Woody tried to enlist in the Marine Corps in 1942, but was told he was too short for service. After the height regulations were changed in early 1943, he successfully enlisted in the Marine Corps Reserve in Charleston, West Virginia, on May 26. On February 21, 1945, he landed on the beach with the 1st Battalion, 21st Marines. Williams, by then a corporal, distinguished himself two days later when American tanks, trying to open a lane for infantry, encountered a network of reinforced concrete pillboxes. Williams went forward alone with his 70-pound (32 kg) flamethrower to attempt the reduction of devastating machine gun fire from the unyielding positions. Covered by only four riflemen, he fought for four hours under terrific enemy small-arms fire and repeatedly returned to his own lines to prepare demolition charges and obtain serviced flame throwers. At one point, a wisp of smoke alerted him to the air vent of a Japanese bunker, and he approached close enough to put the nozzle of his flamethrower through the hole, killing the occupants. These actions occurred on the same day that two flags were raised on Mount Suribachi, and Williams, about one thousand yards away from the volcano, was able to witness the event. He fought through the remainder of the five-week-long battle even though he was wounded on March 6 in the leg by shrapnel, for which he was awarded the Purple Heart. For 70 years, Woody never returned to Iwo Jima. Disappointed by President Lyndon Johnson's decision to return Iwo Jima to the Japanese in 1968, he refused to go to annual "Reunion of Honor" ceremonies on the island. His grandchildren convinced him to return for the 70th anniversary of the American victory. He had such a good time he returned for the 73rd anniversary in March of 2018. Today, Woody Williams continues to live in his native state West Virginia. One of his grandson's serves as the State Funeral for World War II Chair in Kentucky and another serves a the Chairman in Ohio. |

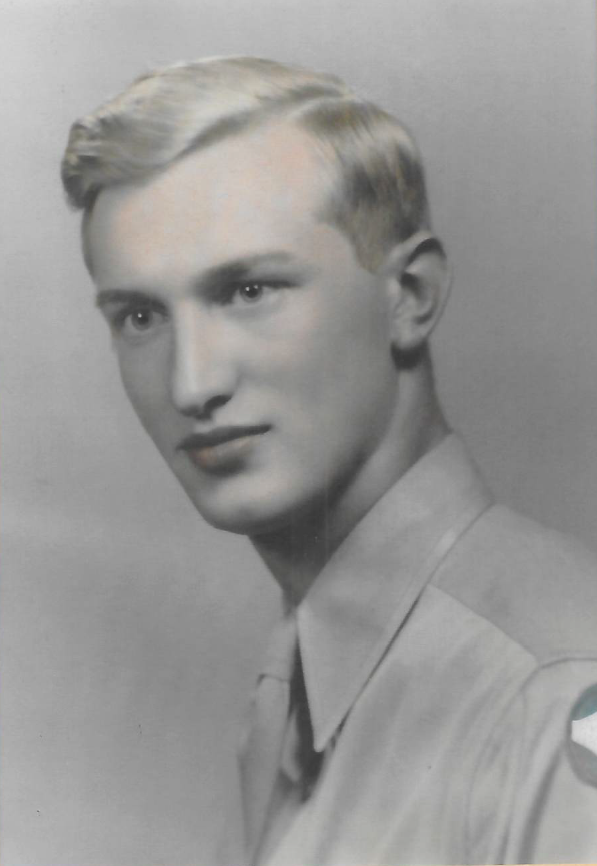

| L. William McNutt, Jr., by Anonymous, August 2017 Bill McNutt, Jr.’s military service in World War II was in many ways different from typical veterans. Not every veteran of World War II faced a bullet or served in combat, but they all took the same solemn oath to defend our country. McNutt grew up during The Depression in Corsicana, Texas, home of the first oil well west of the Mississippi river. "Two things I remember about The Depression and my childhood, were the day we lost our family automobile, and the day we got it back a few years later," said McNutt. Bill McNutt played center and middle linebacker on Vanderbilt's last undefeated football team in 1942 and joined the U.S. Army in 1943. "Because I had a year of college, the Army made me a teacher and I set up a school in a big military tent in Mississippi to teach African America soldiers to read and write” said McNutt. Later he guarded General Rommel's Afrika Korps at a POW Camp in Louisiana. When the Afrika Korps were trapped between the British Forces in Egypt and the American's landing in Algeria, Rommel wanted to evacuate troops before the inevitable happened, but Hitler expressly forbade it. Rommel was flown out of North Africa. Soon after, 130,000 Germans surrendered and by May 1943 the war in North Africa was over. Thousands of these elite soldiers were put in the hole of ships in Tunisia, transported to the port of New Orleans, and later went by train to their newly constructed POW Camps in Louisiana. "They were fine soldiers. After ten days in the holes of those ships, they fell into precise formation and goose stepped into camp,” said McNutt. Sergeant McNutt said they would find a dead German every few weeks, killed by one of their own. "If any Wehrmacht soldiers expressed any thought that Germany was losing the war, they would execute them," said McNutt. The POW's were given a German language copy of the Sunday New York Times each week. They did not believe a word of it and thought it was a propaganda sheet! At the war's end he served as a pay clerk at Ft Dix, New Jersey, mustering veterans out of the U.S. Army. Up until his death to cancer at the age of 81 in 2006, he could recite, by memory, the annual and monthly salary of a private all the way up to a 5 star general, including the three highest paid members of the American Military, Generals George Marshall, Douglas MacArthur, and Dwight Eisenhower. "It was the greatest bargain in the American history," said McNutt, "The tax payers paid them $13,600 a year to defeat the Axis powers!” At the time of his death, McNutt was a member of the First Baptist Church in Corsicana, Texas where he was elected to the city council. He was elected to the Texas Business Hall of Fame, the North Texas Soccer Hall of Fame, and was a Co-Founder with Lamar Hunt of the North American Soccer League. He was an owner of the Dallas Tornado and the Tampa Bay Rowdies. He had four children, Melanie, Katherine, Bob, and Bill. At the time of his death, he also had two grandsons, Thomas Nygaard McNutt and Lee William McNutt, IV, a Marine Corp trained officer in the Texas National Guard. |

| "State Funeral for World War II Veterans" is a registered 501(c)(3) non-profit organization. Donations are tax-deductible to the full extent of the law. Tax ID: 82-1730871. |